In the mid-20th century, as modernism reconfigured architecture’s aesthetic vocabulary, a Spanish-born, Mexico-based architect and engineer was quietly revolutionizing our understanding of structure itself. Felix Candela did not build towers of steel and glass or heroic facades of stone. He sculpted air. Using thin-shell concrete and doubly curved geometries, Candela transformed raw materials into seemingly weightless forms that are expressive, efficient, and profoundly economical.

Candela’s designs, many of them built between the 1950s and 1970s, were not merely architectural statements. They were technical essays written in reinforced concrete. Working with paraboloids, hyperbolic surfaces, and ruled geometries, he elevated structural engineering into an art form. His legacy lies in the convergence of form and force, a structural logic that remains a masterclass for architects and designers today.

The most iconic of his works, from the Los Manantiales Restaurant in Xochimilco to the Cosmic Rays Pavilion at the Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, are not only visually striking but radically thin. These shells, often just a few centimeters thick, demonstrate that structural elegance does not come from mass, but from geometry and precision. In an age of increasing material scarcity and climate responsibility, Candela’s work holds vital lessons for the next generation of designers.

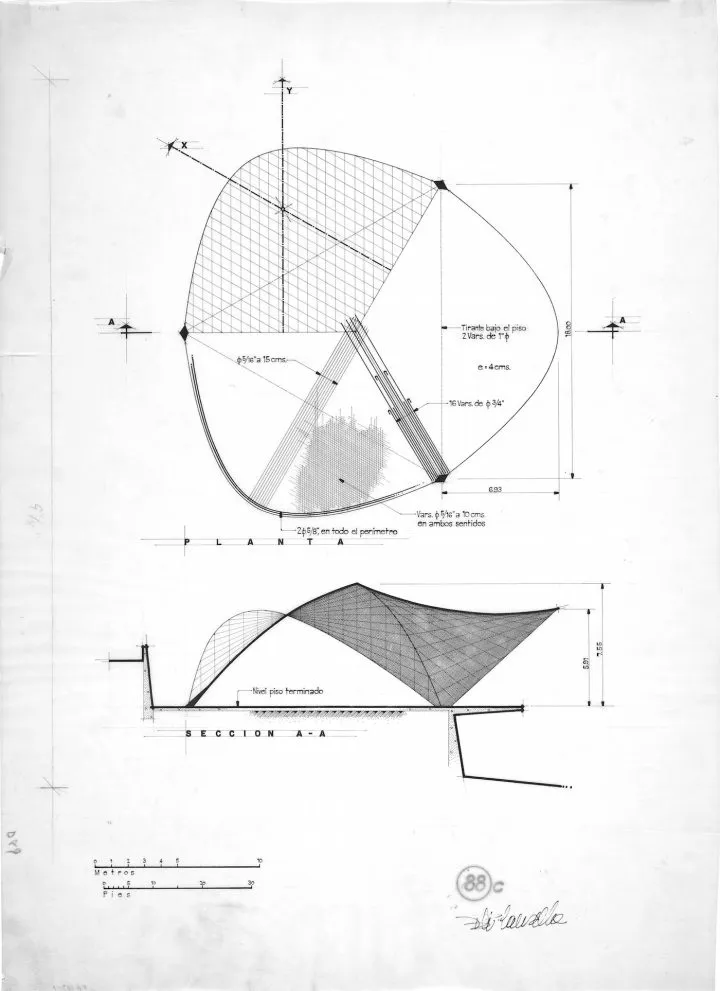

Félix Candela’s 1957 plan for La Jacaranda Cabaret, Presidente Acapulco Hotel in Acapulco, Guerrero

At the heart of Felix Candela’s approach was a profound belief in form-finding, the idea that the shape of a structure should be derived from the natural flow of forces within it. Long before the advent of parametric software or simulation tools, Candela used simple physical models and ruled surface geometry to discover the optimal paths of compression and tension.

His favored form was the hypar, the hyperbolic paraboloid, a doubly curved surface that can be generated with straight lines. This gave Candela a geometric language that was structurally efficient, visually dynamic, and surprisingly simple to construct. Workers could build complex-looking forms using straight wooden formwork and standard rebar techniques. This combination of mathematical precision and construction pragmatism made his architecture both expressive and accessible.

Candela’s form-finding process was intuitive but rigorously rational. He blended engineering knowledge with architectural intent, never sacrificing beauty for performance or vice versa. His ability to “think in curves” allowed him to minimize the amount of concrete needed while maximizing span, lightness, and spatial drama.

Felix Candela was not alone in his exploration of thin-shell structures. He belonged to a broader movement of structural pioneers such as Frei Otto, Pier Luigi Nervi, and Heinz Isler. But what sets Candela apart is the seamless integration of design economy, visual poetry, and construction logic. His architecture offers multiple layers of learning:

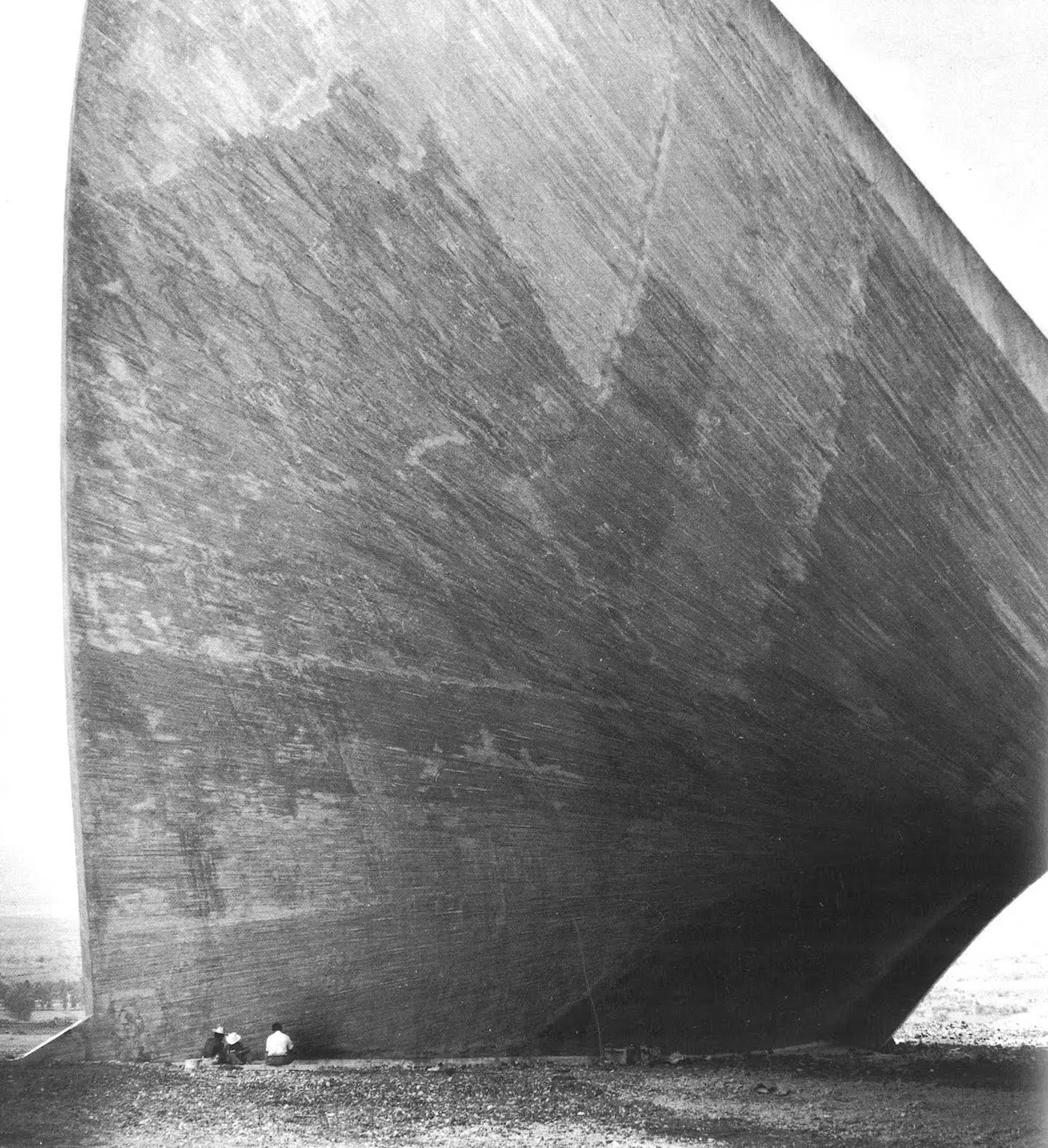

One of his most recognized works, the Los Manantiales Restaurant (1958), features a four-leaf clover shell supported by a central column. Its geometry is both structurally optimal and spatially sublime. The curvature allows the shell to carry loads efficiently to the ground while creating a canopy-like enclosure that invites air, light, and shadow to animate the space throughout the day.

Workers constructing the concrete shell at Restaurante Los Manantiales in Xochimilco, Mexico City in 1958

Today’s architects have access to advanced digital tools that can simulate and model complex forms in seconds, tools that Candela could have only dreamed of. But these same tools often generate complexity for its own sake, rather than structural or material intelligence. This is why Candela’s work remains so relevant. It teaches restraint, efficiency, and the importance of letting geometry serve a purpose.

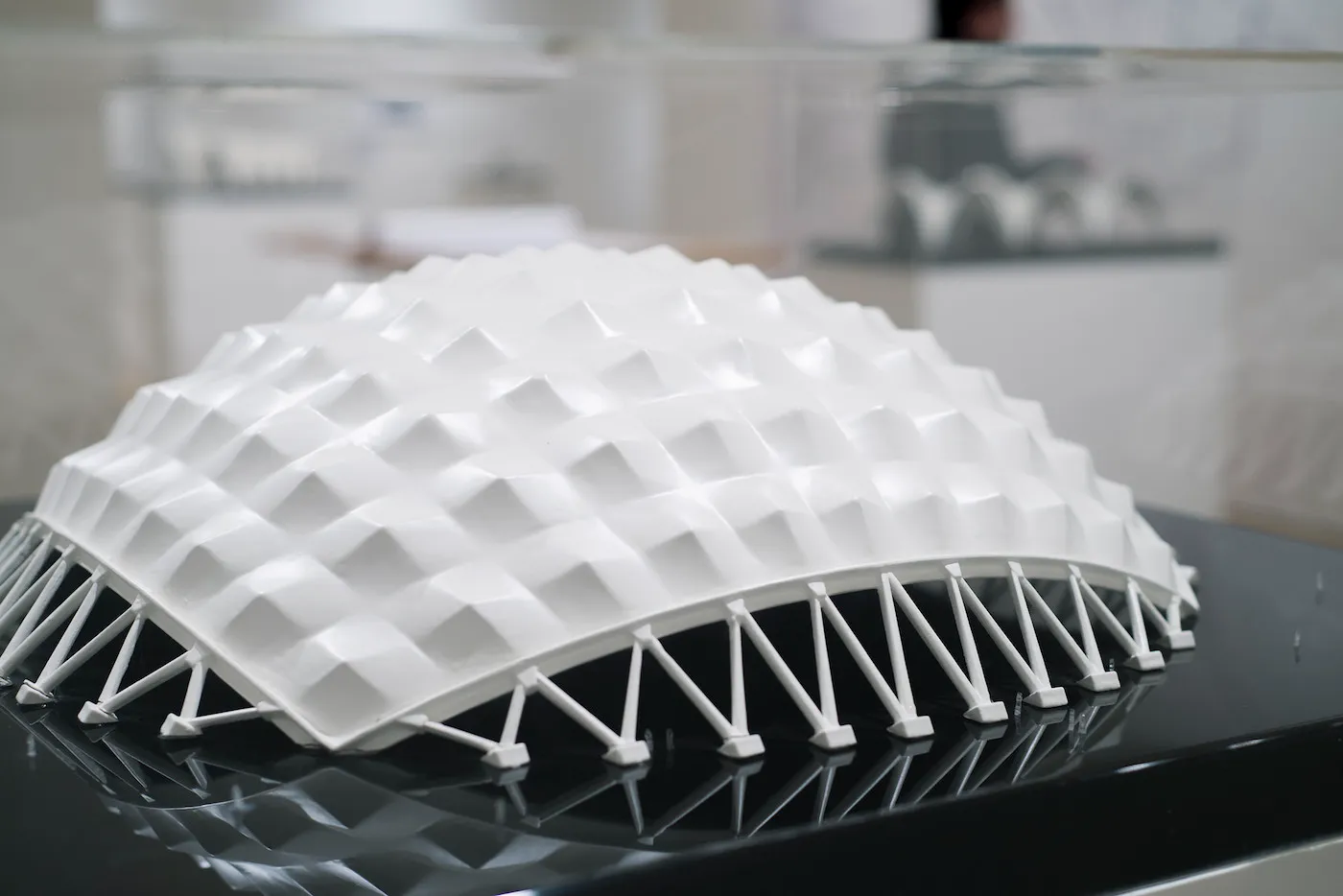

.webp)

Installation view of ‘Félix Candela’s Concrete Shells’ at Gallery 400

For contemporary designers interested in performance-driven architecture, Candela’s lessons are especially powerful:

Start with structure, not surface: Let the flow of forces define the envelope.

The re-emergence of interest in digital form-finding, parametric modeling, and sustainable construction is in many ways a return to Candela’s principles. Studios exploring generative structures, robotic concrete casting, or shell-based prefabrication are operating within the territory he helped map, only now with new tools and materials.

Installation view of ‘Félix Candela’s Concrete Shells’ at Gallery 400

Felix Candela’s work remains one of the most graceful examples of how geometry and gravity can collaborate. His buildings appear lightweight, almost alive, not because of ornamentation but because of how intelligently they are shaped. They resonate with architects, engineers, and students alike — not as monuments to complexity, but as testaments to clarity.

In a time when the architectural world is wrestling with digital excess, climate urgency, and construction waste, Candela’s legacy reminds us that the answers may lie not in bigger gestures but in smarter ones. His forms are not nostalgic relics of modernism; they are blueprints for the future.

For those who seek architecture that is rigorous, expressive, efficient, and enduring, Felix Candela is not just a historical figure. He is a guide.

Today, Candela’s analog form-finding principles are echoed in modern computational tools. For those interested in exploring how digital design can build upon these foundations, the Scripting Forms: Grasshopper3D & Blender workshop at PAACADEMY offers a hands-on approach to structural expression through simple scripts and geometric logic.

Félix Candela’s Chapel Lomas de Cuernavaca in Morelos, Mexico in 1959

You must be logged in to comment.