Exploring the historical and epistemological trajectory from Alberti’s vision of architecture as notational authorship to the procedural automation of BIM, this essay addresses how the architectural drawing has become a machinic protocol, a system that encodes, executes, and governs. The architect becomes a cognitive agent embedded within an optimized system of parameters, scripts, and simulations, in which architecture no longer represents thought but performs it.

Yet right from the start the spirit of the Albertian design process, which aimed at the identical materialization of the architect’s design of a building, was already, in a sense, mechanical. In today’s terms, Alberti’s authorial way of building by notation can be interpreted as an ideally indexical operation, where the architect’s design acts like a matrix that is stamped out in its final three-dimensional result—the building itself.

— Mario Carpo, The Alphabet and the Algorithm (2011)

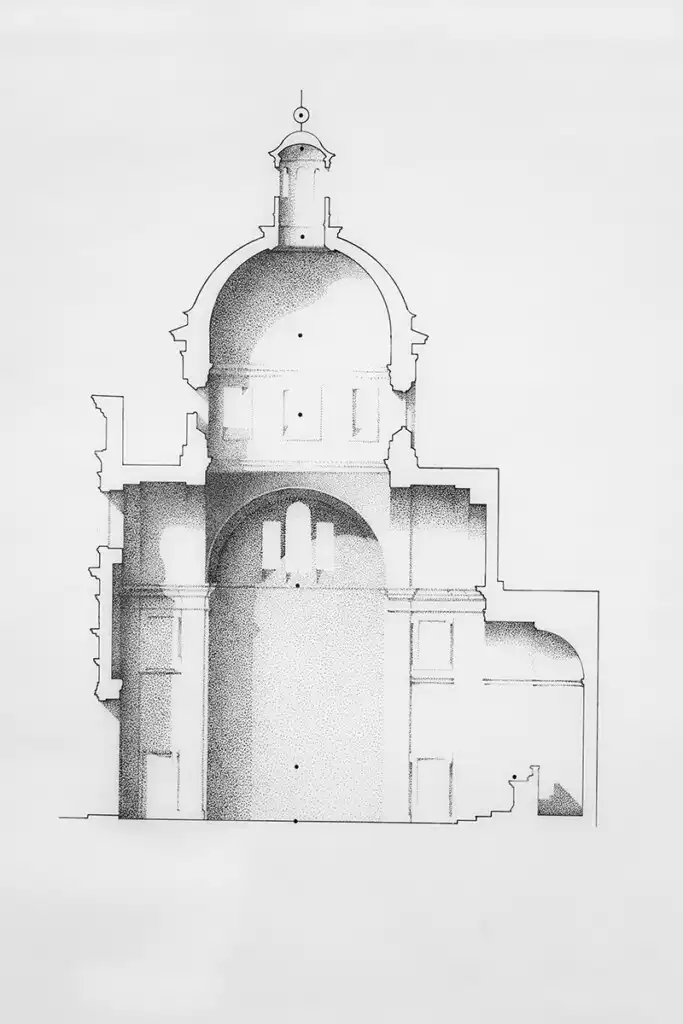

Encoded to be executed, buildings are no longer drawn to be seen. Alberti envisioned architecture not as a craft but as a reproducible code. According to Carpo, Alberti’s pursuit of perfect copies marked a quiet revolution, a moment when art, science, and the shaping of culture began to follow the logic of repetition. His idea of “building by notation,” where drawings become the silent scripts of buildings, still echoes through the practice of architecture today. The ambiguity inherent in architectural representation is underscored by Evans' assertion that “a great deal in architecture may be language-like without being language.” Unlike linguistic systems, architectural drawings lack a fixed grammar or vocabulary.

They imply rather than instruct, suggest rather than state. This persistent tension, between symbolic form and material execution, continues to complicate the translation from design to building, even within today’s data-driven design environments. In his reading of de l’Orme, Robin Evans exposes a critical epistemic illusion: that verbal affirmation coupled with visual impression suffices as proof. This reliance on the alignment of word and image reflects a deeper tradition in Western thought, where similarity is equated with truth, and representation with knowledge.

In the era of BIM, this logic remains intact: when parametric data corresponds with rendered form, the illusion of accuracy is sustained. But as Evans reminds us, correspondence is not emancipation, it is manipulation disguised as clarity. Following Evans, BIM reconfigures the architect's role within a machinic matrix, not as a creator of form, but rather as a curator of parameters. BIM is not merely a technical tool; it is a virtual execution regime that reconfigures the entire professional structure prior to material reality.

As a system of clarity and coordination, BIM operates by replacing interpretive ambiguity with quantifiable certainty. The model no longer serves as an aesthetic instrument but as an operational platform, one that generates quantities, schedules, and simulations. Drawings, in this context, are no longer expressive; they become encoding protocols within a machinic logic. Architecture shifts from being imagined to being executed.

As Daniotti et al. note in BIM-Based Collaborative Building Process Management, “The paradigm of the fourth industrial revolution (Industry 4.0) involves data management and the interconnection between machines, objects, people, and processes. The keywords of the revolution underway are: information in real environments (AR); data management (Big Data and AI); digital collaboration; intelligent objects (IoT); and additive manufacturing (3D printing).”

Within this context, the architect emerges as a distributed cognitive node, a procedural agent embedded within the machinic protocols of design. They no longer operate as an autonomous author of form; rather, their role is redefined through acts of curation, coordination, and algorithmic execution across regulated information flows within the realm of BIM.

Extending beyond buildings to cartographic representation, Alberti’s commitment to identical reproducibility can be regarded as proto-parametric. In his Descriptio urbis Romae, he proposed a technique that enabled readers to reconstruct a map of Rome from a specific vantage point using only linear and angular measurements. Dissolving into code long before the digital, geometry here becomes a language of instruction, a system for transmitting form without drawings.

Luciana Parisi explains that digital algorithms are not just tools that represent data. Instead, they actively shape how information is processed, according to their own internal logic. This process does not fully follow standard systems like binary code, nor is it entirely governed by external inputs. Algorithms respond both to the formal systems they are scripted into and to the data they retrieve, yet this does not result in simple repetition.

Rather, the information is transformed as it passes through them, like a chain reaction or a kind of contagion. In BIM, we do not code representation; we code formation. The architect no longer “creates” form directly, but instead defines the parametric space from which it will emerge. The drawing becomes a scene of operation, not a plan. It does not represent thought; it produces it.

Architecture is no longer assembled from discrete elements; it is deployed through systems, standardized, optimized, and automated to execute. The architect no longer acts as the author of form, but as a cognitive interface within the system, a decoding function embedded in the machine itself.

Apple Park, designed by Foster + Partners, exemplifies how BIM transcends representation and becomes an engine for execution. In this continuous circular form, BIM served as a procedural interface, governing the flow between design, material computation, and physical realization.

The project’s components were not designed individually but orchestrated through scripts and sequences embedded in the model. The execution of the building’s shell and core was undertaken by DPR and Skanska, while Arup provided integrated engineering consultancy, aligning the technical systems with the project’s highly synchronized, data-driven environment.

Alberti, Leon Battista. On the Art of Building in Ten Books. Translated by Joseph Rykwert, Neil Leach, and Robert Tavernor. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1988.

Carpo, Mario. The Alphabet and the Algorithm. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2011.

Evans, Robin. “Translations from Drawing to Building.” In Translations from Drawing to Building and Other Essays, 153–193. London: Architectural Association, 1997.

Parisi, Luciana. Contagious Architecture: Computation, Aesthetics, and Space. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2013.

Daniotti, Bruno, Alberto Pavan, Sonia Lupica Spagnolo, Vittorio Caffi, Daniela Pasini, and Claudio Mirarchi. BIM-Based Collaborative Building Process Management. Springer Tracts in Civil Engineering. Cham: Springer, 2020.

Eastman, Chuck, Paul Teicholz, Rafael Sacks, and Kathleen Liston. BIM Handbook: A Guide to Building Information Modeling for Owners, Managers, Designers, Engineers and Contractors. 2nd ed. Hoboken, NJ: Wiley, 2011.

You must be logged in to comment.