Frei Otto did not see architecture as a matter of form-making, but as a process of listening to gravity, to materials, to wind, and to water. While the second half of the 20th century celebrated steel towers, glass boxes, and concrete monuments, Otto pursued something quieter, lighter, and far more radical. His vision was not to conquer nature but to collaborate with it. His buildings stretched, floated, and hovered, revealing the beauty of minimal intervention and maximum intelligence.

Born in 1925 and trained as both an architect and structural engineer, Frei Otto became a pioneer in lightweight construction and the exploration of tensile structures. Rather than drawing buildings in plan and section, he experimented with soap films, hanging chains, and stretched fabrics. These analog experiments were not metaphors; they were physical models that directly informed his designs. Otto believed that the most efficient forms could be found, not imposed, and that nature had already solved the problems architects were trying to answer.

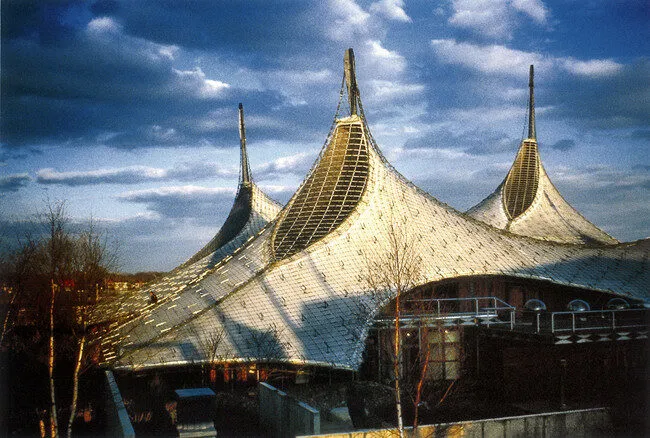

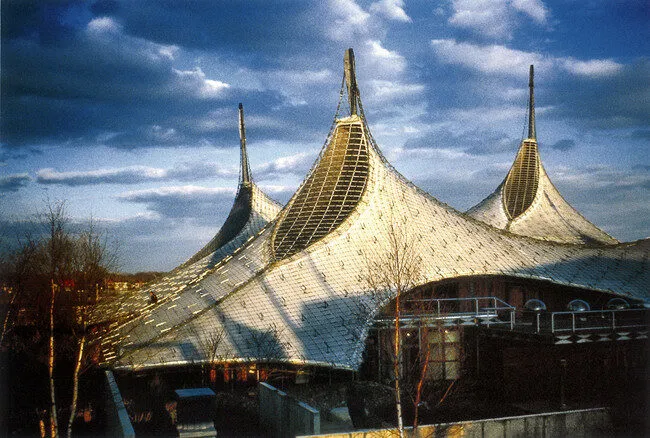

His influence is not confined to any single style or movement. From the tent-like roof of the Munich Olympic Stadium to the experiments at the Institute for Lightweight Structures in Stuttgart, Otto’s work redefined what architecture could be. In 2015, just weeks before his passing, he was awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize, recognizing not just a lifetime of work but a philosophy that continues to resonate with contemporary architects exploring form-finding, biomimicry, and sustainable design.

Frei Otto’s work was not only about aesthetics or structure. It was about ethics, adaptability, and ecological responsibility, ideas that feel more urgent today than ever before.

At the core of Frei Otto’s process was the concept of form-finding. Unlike form-making, which starts with an idea or vision and then seeks ways to realize it, form-finding is about discovering geometry that emerges from physical laws. Otto used a wide range of experimental tools to test this approach, including soap film models, which naturally form minimal surfaces when stretched between boundaries.

Soap films are not only beautiful; they are instructive. They reveal how surfaces behave under tension, how curves distribute forces, and how minimal material can span space efficiently. Otto applied these principles to architectural form through physical modeling, photography, and later computational simulation. His process anticipated many digital techniques used today in parametric design, but it was tactile, intuitive, and grounded in physical truth.

One of his famous quotes encapsulates this philosophy: “I have built little. But I have built something you do not see: I have built up an idea.” That idea was architecture not as a finished object, but as a responsive system, one that is adaptive to force, climate, and purpose.

Among Otto’s most recognizable works is the roof of the Munich Olympic Stadium (1972), co-designed with Behnisch & Partners. Its vast canopy of tensioned steel cables and transparent membranes redefined what a stadium could be. Rather than a heavy bowl, it became a transparent, floating landscape, democratic, dynamic, and humane. The undulating form was derived from physical models and tested under various loads, making it one of the earliest examples of computationally-informed structural design, even before the digital age took hold.

Another landmark project is the German Pavilion at Expo 67 in Montreal, which featured a tensile net roof suspended by masts and cables. The pavilion was a masterclass in modular design and minimal surface structure, achieving both elegance and economy. Its geometry was not arbitrarily drawn but discovered through form-finding experiments using netting and elastic fabrics.

.webp)

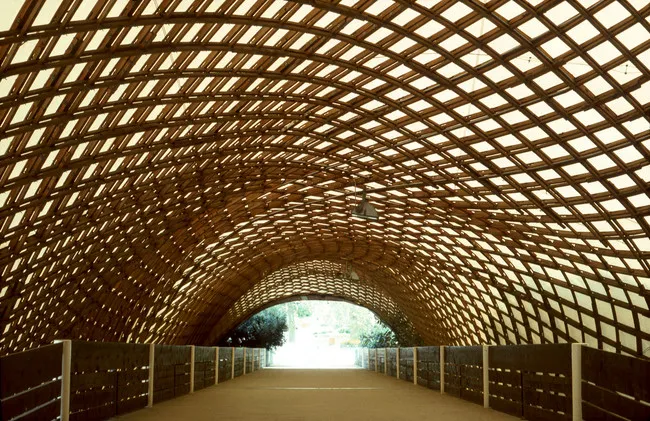

Otto’s Multihalle in Mannheim (1975), designed with architect Carlfried Mutschler, pushed the limits of timber construction. It featured a freeform grid shell composed of slender wood beams, demonstrating how curvature and lightweight logic could coexist with natural materials. Despite its complexity, the construction process was relatively simple due to Otto’s rigorous testing and modeling.

In addition to his built work, Otto established the Institute for Lightweight Structures at the University of Stuttgart, where he mentored generations of architects and engineers. This research lab became a breeding ground for innovation, exploring materials like pneumatic membranes, grid shells, and air-supported structures long before they became mainstream.

Frei Otto’s legacy is not simply technical, it is philosophical. His belief that architecture should be resource-conscious, socially engaged, and derived from the logic of forces offers valuable lessons for the future. As the architecture profession grapples with climate change, rapid urbanization, and digital complexity, Otto’s ideas feel more like a blueprint than a relic.

Here are a few key takeaways from his work:

Otto’s work also laid the groundwork for many of today’s most exciting architectural movements. The rise of biomimetic architecture, digital form-finding tools like Kangaroo Physics in Grasshopper, and projects by firms like SOM, Grimshaw, and Zaha Hadid Architects all reflect Otto’s DNA, whether explicitly acknowledged or not.

While Otto worked mostly with analog methods, the principles he championed have found fertile ground in computational design. The form-finding logic used in his soap film experiments is now embedded in software that simulates physical forces and material behaviors. Architects can now digitally generate and test structures using parameters and feedback loops that mirror Otto’s hands-on approach.

Yet even with all these tools, the core question remains: What kind of architecture should we be making? Otto reminds us that the answer lies not just in form, but in values. He advocated for a shelter that was light on the earth, democratic in intention, and poetic in performance.

His vision was never confined to what could be built. He imagined refugee shelters, floating cities, and utopian campuses long before sustainability became a mandate. He believed that architecture could, and should, serve more than the privileged few. In many ways, Frei Otto was a humanist disguised as an engineer.

Frei Otto taught the world that the lightest structures often carry the most profound ideas. He revealed that architecture does not need to dominate space to define it, that efficiency can be beautiful, and that nature offers all the inspiration we need if we pay attention.

For architects and engineers today, his legacy is not just one of shapes and structures, but of curiosity, ethics, and elegance. His buildings still seem futuristic, yet they are grounded in some of the oldest forces we know: gravity, tension, wind, and light.

In an era when the built environment is called upon to respond with agility, restraint, and intelligence, Frei Otto’s architecture stands not as a style but as a way forward.

You must be logged in to comment.