Zaha Hadid was born in Baghdad, Iraq, on October 31, 1950. After completing her architectural education at the London Architectural Association, she began working at the Office for Metropolitan Architecture, of which she was also a partner, in 1977. In 1979, she founded her own firm, Zaha Hadid Architects (ZHA), based in London. Early in her career, Hadid had the opportunity to teach at many prestigious universities, including Harvard University, the University of Illinois, the Hochschule für Bildende Künste in Hamburg, and the Knowlton School of Architecture. Before her death, she was a professor at the University of Applied Arts in Vienna and an honorary member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Hadid has developed groundbreaking projects as the winner of many international competitions. Since her designs were generally considered to be ahead of technology, many of her projects could not be built at first. However, with the development of technology over time, the importance of curves in architecture began to be understood, and Zaha Hadid began to be known as the "Queen of the curve."

In 2004, she won the Pritzker Prize and was given the title of the world's "greatest female architect," and it was stated that her work transcended gender distinctions. She was also awarded the Order of the British Empire (CBE) for her contributions to architecture before the Pritzker Prize. In 2008, Hadid was ranked 69th on Forbes magazine's "World's 100 Most Powerful Women" list and was considered one of the key figures of architecture in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

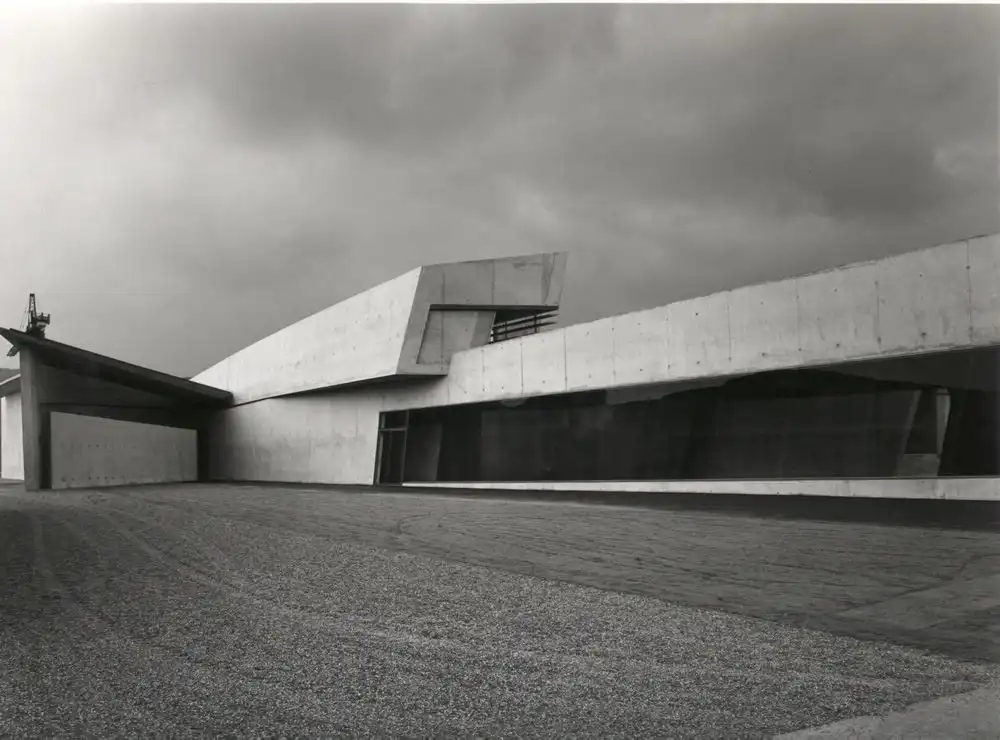

Zaha Hadid, known for her “deconstructive” designs, adopted a postmodernist style that fragmented and manipulated forms to create unexpected works. She developed innovative approaches by blending mathematics and architecture in her designs; at this point, her education in mathematics at the American University of Beirut is considered an important factor. The first important application project in Hadid’s career was the Vitra Fire Station, which she built in 1993. Constructed of exposed concrete, this structure is currently used as a museum building displaying Vitra’s chair designs.

Zaha Hadid drew inspiration from the aesthetics of Arabic calligraphy to create her fluid forms, blending traditional Islamic architecture with modern times to design non-hierarchical spaces. In addition to using curves to push the boundaries of spatial configuration, she also introduced lined surfaces that questioned tradition in her interior designs.

Zaha Hadid’s architecture office operates in London and has over 350 employees. After her untimely death in 2016, Hadid’s legacy continues to live on under the leadership of Patrik Schumacher, the creative partner of Zaha Hadid Architects and continues to be one of the world’s top architecture firms.

Zaha Hadid’s first completed structure, the Vitra Fire Station, was initially designed as a fire station, but over time, it was expanded with additional functions such as a bicycle park, training area, and perimeter walls. The project, which began in 1989, was completed in 1993. The building was designed in a narrow and long form that extends along the street in harmony with the linear agricultural fields around it. Thus, it became an architectural element that defines and delimits the area rather than an isolated object.

The geometry of the building is derived from the intersection of the directions of the surrounding factories and agricultural areas and the direction of the railway. The structure is shaped by sharp corners, angles, and breaks that reflect these opposing axes. The station, which creates a simple and powerful effect with its exposed concrete material, represents a frozen movement, like a team that must always be on alert. The walls on the exterior are arranged in a way that gives the impression of shifting by sliding; the large sliding doors reinforce this dynamic feeling.

The interior spaces can only be perceived from certain angles, and when viewed from the outside, not much is visible except for the large fire engines. The windows are unframed and free of details; the roof edges and connecting elements are almost invisible. This approach aims to preserve the sharp, prismatic, and sculptural character of the structure.

The 270-meter-long Zaragoza Bridge Pavilion served as both a pedestrian crossing over the Ebro River and an exhibition pavilion during the Expo in Spain. It is Zaha Hadid’s first completed bridge design. Inspired by a gladiola flower, the bridge is composed of four structural sections. These sections are covered with triangular fiber cement panels that intersect and support each other, creating distinct enclosures. Two large sections are designed as fully enclosed main exhibition galleries, while the other two sections are covered with a single-layer cladding that leaves the steel structure exposed.

These sections of the bridge are illuminated by small triangular windows that provide views over the water. Approximately 62,500 prefabricated steel elements were used in its construction. Zaha Hadid described the project as “a pioneering study in practice,” emphasizing that “our passion for creating fluid, dynamic, and complex structures is supported by technological innovation.” The Bridge Pavilion is an example of this innovative approach, pushing the boundaries of architecture.

Zaha Hadid’s MAXXI: Museum of XXI Century Arts is described as “not an object-container, but a campus for art.” Dynamic paths and flows overlap to provide visitors with an interactive experience, while flexible spaces create a suitable environment for various temporary exhibitions. The museum’s interior is shaped by elements such as curved concrete walls, suspended black stairs and an open ceiling that lets in natural light. This design offers a fluid spatiality consisting of multiple perspective points and fragmented geometries created to “embody the chaotic fluidity of modern life.”

Hadid’s design has been criticized for its relationship with Rome’s classical heritage. While the curved walls establish a dialogue with the neoclassical symmetrical façades, the museum finds its place as a part of the urban fabric. Thin concrete beams on the ceiling provide natural lighting with glass cladding and filtering systems, while rails for the artworks are suspended from these beams. Visitors are directed to the spacious area on the third floor, where they can enjoy a view of the city from a large window. Thus, the MAXXI Museum reflects the modern face of Rome by establishing an active relationship with both the past and its surroundings.

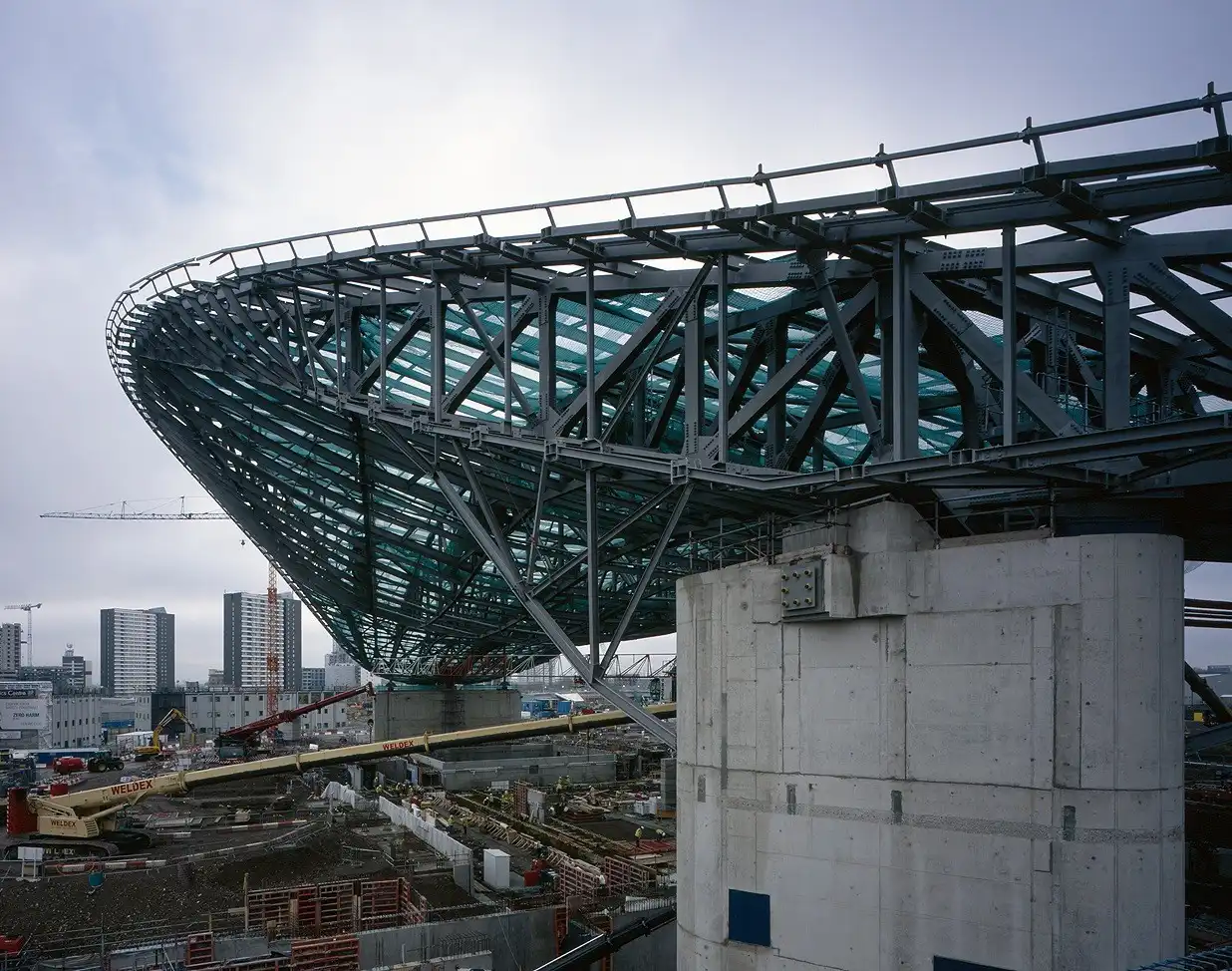

The design of the London Aquatics Centre is inspired by the fluid motion of water, creating a dynamic form that blends into the riverside landscape of the Olympic Park. Its undulating roof is designed to resemble a wave of water rising from the ground, both enclosing and defining the volume of the swimming and diving pools. The structure was designed to hold 17,500 people for the 2012 London Olympics, with the flexibility to be reduced to 2,000 people for permanent use after the Games.

The centre is located on the southeast side of the Olympic Park, close to Stratford. The Stratford City Bridge, which crosses the structure, provides new pedestrian access to the park and makes the centre’s location the main entrance to the park. The design takes into account the public realm connections in the park and urban planning, creating an integrated urban network with the park’s canals and bridges.

Designed by Zaha Hadid Architects, the Riverside Museum is located on the banks of the River Clyde in Glasgow. The 7,000 square metre museum features exhibitions focusing on the history of transport, as well as a café, shop and educational spaces.

The Riverside Museum, Glasgow Photo By: Alan Mceeter

The museum establishes a strong connection with the Clyde and the historical development of Glasgow. The structure, which forms a transition area between the river and the city, is positioned as a symbolic bridge that unites these two elements. Its tunnel-like form opens up to both the river and the city, thus establishing a strong relationship with the context. The interior offers a fluid experience that transports visitors from the outside world to the world of the exhibitions.

The Broad Art Museum is located at a key intersection between the Michigan State University campus and the city of East Lansing. The museum’s design was inspired by pedestrian movements and visual connections in this area. The planes fold and twist in three-dimensional space, creating a dynamic interior landscape that directs circulation and brings together different routes.

This design approach allows curators to create many different perspectives and relationships when organizing an exhibition. The sharp-edged, faceted form of the building responds to the surrounding topography and flow of movement. Its exterior has a surface that constantly changes from different angles and does not fully reveal the building’s content. This mysterious stance makes the museum not only an exhibition space but also a cultural center that evokes curiosity and establishes a strong connection with its surroundings.

Galaxy SOHO is designed as a 330,000 m² office, retail and entertainment complex in the heart of Beijing. Connected by bridges, the project offers a panoramic architectural composition free of sharp corners. The sinuous forms of the structure flow in continuous harmony with each other; this fluidity is supported by large interior courtyards inspired by traditional Chinese architecture. The plateaus and transitions within the volumes give the user a deep sense of immersion, turning the experience of the space into a discovery.

While the lower floors are dedicated to public shopping and entertainment areas, the upper floors host creative workspaces. At the top, bars, restaurants, and cafes open up to the city view and offer a space integrated with social life. With its fluid form and functional diversity, Galaxy SOHO is not just a building but a contemporary living center and urban icon that is in constant communication with the city.

Designed by Zaha Hadid, the Heydar Aliyev Center is one of the cultural symbols of Azerbaijan, offering an alternative language to the rigid and monumental Soviet architecture in Baku. Built after winning a competition in 2007, the structure draws attention with its sinuous and fluid forms that reflect the elegance of Azeri culture and its vision of modernization.

The Heydar Aliyev Center design creates a seamless transition between the urban square, which is the exterior, and the interior. The surfaces rise, undulate, and transform into an architectural landscape that guides both the exterior and interior. Thus, the building blurs the distinctions of interior/exterior, figure/ground, and object/landscape. This fluidity brings a contemporary interpretation to the order and rhythm of Islamic architecture, providing a cultural continuity without being stuck in the past.

The center was built with a combination of reinforced concrete and space frame systems to create wide-open, column-free interior volumes. Unusual engineering solutions were implemented to support the fluid design; structural elements are bent, and consoles are extended like tails. The lighting design also supports this transition; While the volume changes itself according to the environment in daylight, the lights emitted from inside to outside at night reveal the form of the building.

Jockey Club Innovation Tower (JCIT) is home to the School of Design at The Hong Kong Polytechnic University and the Jockey Club Social Innovation Design Institute. The 15-story, 15,000-square-metre structure accommodates over 1,800 students and staff. It provides a variety of facilities, including design studios, laboratories, exhibition spaces, and multi-functional classrooms, creating an environment that fosters innovation in education. JCIT acts as a hub for interdisciplinary collaboration and social interaction, adding richness to the university’s campus.

The tower’s design transforms the typical tower/podium layout into a more fluid composition. The interior and exterior courtyards combine with large exhibition forums and social spaces, providing opportunities for interaction and gathering. Glass walls throughout the interior provide transparency and connectivity, while circulation paths enhance interaction between different design disciplines. The Hong Kong Jockey Club Charitable Foundation contributed HKD 249 million to this project, also supporting the construction of the Jockey Club Social Innovation Design Institute.

The Antwerp Port House, designed by Zaha Hadid Architects, renovates an abandoned fire station and transforms it into a modern office building. With this structure, port workers, who were scattered around the city, are gathered under a single roof. The new design creates a striking dialogue between the past and the present by adding a “floating” form to the historical structure.

The new additional volume, which is elevated, faces the Scheldt River like the prow of a ship. The glass façade design creates a sparkling surface that changes according to the light. Thanks to the triangular forms, some parts of the façade are opaque, while others are transparent; this provides both light control and a strong visual relationship with the environment. The shiny surface and dynamic form refer to Antwerp’s identity as the “city of diamonds.”

The inner courtyard of the historical structure has been covered with glass and transformed into the main reception area. From here, visitors can access both the historical interiors and the new annex building, which offers panoramic views. The office spaces are organized in both the historical building and the new volume according to an activity-based working model.

You must be logged in to comment.